There’s a lot about the world that art school doesn’t teach you, even if you attended before the Great Intellectual Shutdown, when identity politics rendered almost every college and university illegitimate. But one thing in particular stands out, a lesson only learned with time, and the wisdom that comes with trying and failing.

Sometimes, your work doesn’t sell.

Today is Thanksgiving. It’s only appropriate that I start off with some sincere gratitude.

I’m grateful to be alive, in functionally decent health, and to have, at the moment anyway, a roof over my head.

See, I’ve been unemployed since March of this year, and when you can’t pay your rent, they tend to kick you out into the street. And when you can’t make any money, your health tends to deteriorate due to stress and bad diet, and your self-worth suffers immensely. If you’re not careful, you can give up on yourself. Especially if you’re no longer employed in your field, after having worked for over half your lifetime.

Today I won’t be enjoying any sort of Thanksgiving meal, because I have alienated most of my family and friends with my desperate pleas for financial help over the course of this wretched year. In an endless search for gainful employment, I have been forced to come to terms that there is no difference between the half-insane maniac whose words you read here and the flesh-and-blood guy who dodders around in three-dimensional meatspace farting in grocery stores. I accept, for better or for worse, that this is who I am. That said, I wouldn’t want to hang out with that guy either.

I’m thankful that there are still people out there who understand my commitment to lifetime artistic achievement. And, over the course of a lifetime, stocks rise and fall, and this applies to artistic stocks as well. Ideas go in and out of favor, as do ideologies and more rigid schools of thought. Teaching methods change, and adapt to the ever-dwindling average of attention spans. Some artists keep up, some don’t.

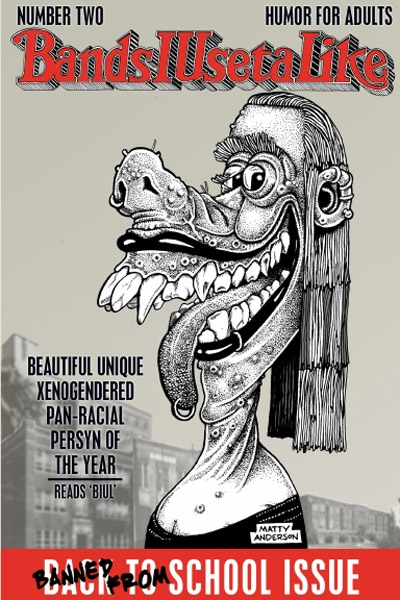

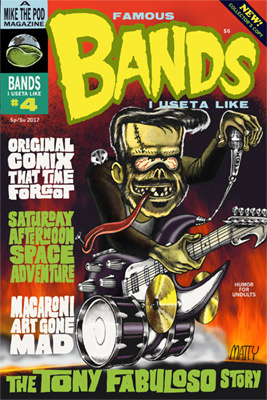

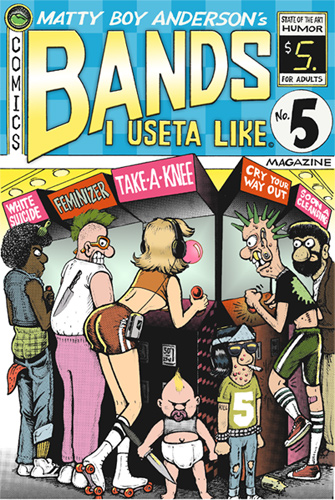

I’m thankful that people have been putting up with this website for ten years, accepting (in general) my most extreme takes, ideas and opinions, and that some generous people have even helped support it monetarily. That is something for which I am quite humbly grateful. I committed to this particularly harsh style of humor over thirty years ago, and because it is perfectly normalized in my perspective, the fact that it may not be to everyone’s taste slips my mind on an hourly basis. I also constantly forget that not every single person in the world wants or needs to know what I think every single day. A quarter-century ago, I was given the opportunity to communicate with millions of people whenever I wanted, which meant that at any given moment, day or night, the opportunity existed to distract people. It completely rewired my brain as a cartoonist and an entertainer.

Nothing has ever been more important to me than laughter, except for maybe getting stoned and drawing cartoons, and let’s face it; laughter is the entire point of those activities. The unending misery of my financial life is funnier than me riding high on cartoon checks, a pipe dream that no respectable artist is currently enjoying in reality. It makes for more relatable content and comic strips. It’s no fun to inhabit, and everyone hates my guts, but it forces me to take fun wherever I can get it. To appreciate what people think is fun, and why they do. To put that into my work. I’m thankful to be able to see it this way.

In June, when I worked a high-paying temp job among regular folk (“normies”, if you will), I completely concealed my artistic identity and played at being a tight-lipped bookworm. I made no mention whatsoever of my cartoons or websites, completely going against my Barnumian instincts, because this job was in a federal courthouse, and I knew that even the most innocent discussion might get me all blustering and booted. I was so unsociable that the other citizens in my group thought I didn’t like them, which is hilarious because the job lasted two weeks and I still think fondly of working with them. I even remember their first names, which anyone who knows me can tell you, is impossible. (I have a social phobia wherein I’m terrified of saying someone’s name wrong, and I’m in contact with up to seven hundred people at any given time.)

No matter what happens next, I have people who have supported my artistic imprint for decades, both personally and professionally. When you think about the caprices of the au courant, not to mention what a hostile, unsavory character I am (and believe me, there is nothing underneath), that is absolutely something to be thankful for. No one who thinks or behaves like I do lives in a big mansion with lots of friends and a loving wife and three kids. They live in a roach-infested apartment in a blasted-out ethnic ghetto, under constant threat of eviction because they can’t find enough work to pay rent, eating Top Ramen alone on Thanksgiving Day. That is how life rewards people like me.

To be a true cartoonist is to be a jester. Success is not the jester’s lot in life; it is to entertain. Comfortable people don’t strive to entertain others; desperate people do, as a method of demonstrating their worth when money fails to do so. There is value in laughter, often more precious than diamonds. However, the value is obtained only through the action, not the object, it cannot be possessed, and it requires at least one other human being to work properly.

This is why the jester can be oversensitive, and oftentimes cannot take a joke.

Because the jester is the joke.

The jester lets it get to him when others criticize him, even if they are strangers he’ll never meet again, because they are his audience. Their opinions and feelings, by association, matter to him. A negative assessment or comment means an unhappy audience member. It hurts the jester in a way that no one else can ever understand, the pain of a heart wounded most deeply. Nevertheless, in mere hours, all evidence of this hurt is forgotten. Often by both parties, unless a detailed reminder is utilized.

When someone points out that the jester is poor, even after decades of loyal service, it makes the jester feel as though he has wasted a life better spent building houses or raising a family, despite never craving those things before. It drives the jester into fits of bad behavior, like drinking, fighting, or carousing, before he remembers to use his resentment and anger as fuel to be funnier.

Then the jester gets back in front of that king’s court and he does his goddamnedest to make ’em laugh again.

Because that’s his motherfucking job.

Happy Thanksgiving. Here’s to a better one. Thank you for being there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.